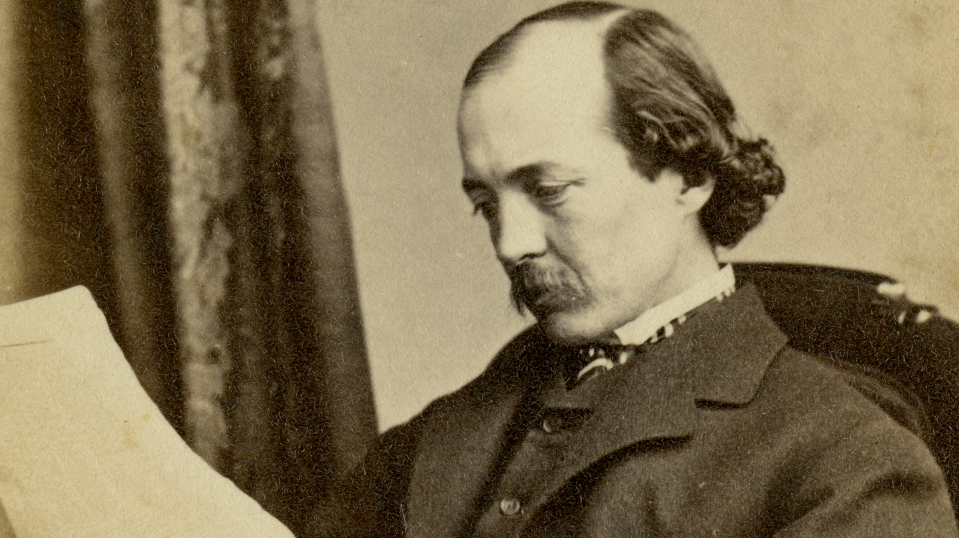

History of the nature and well-being movement: Frederick Law Olmsted

The importance of access to green space for all

American land architect Frederick Law Olmsted was a pioneer in establishing city parks and park systems connecting cities with green spaces. He was perhaps best known for his design of New York’s Central Park. He was also a conservationist and passionate advocate that common green spaces be accessible to all for the benefit of the public’s wellbeing.

In 1865 he wrote a report recommending that Yosemite, an area of natural beauty, be placed under State control and designated as a national park.i

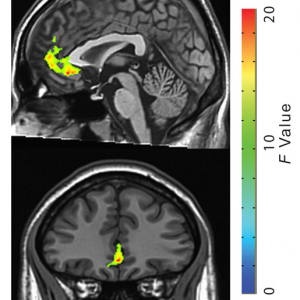

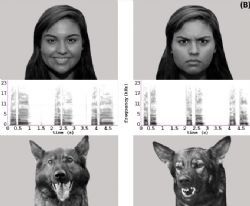

In his leading argument he stated that Yosemite should be preserved as a park for the good of the nation to allow all citizens the pursuit of happiness. Olmsted asserted that spending time in natural settings was good for physical and intellectual health and increased happiness both in the moment and afterwards. Indeed Olmsted declared these benefits as ‘scientific fact’ over a century before modern science, using MRI scans, proved that simply viewing images of natural scenery reduced stress and anxiety.ii

Olmsted wrote,

“It is a scientific fact that the occasional contemplation of natural scenes of an impressive character, particularly if this contemplation occurs in connection with relief from ordinary cares, change of air and change of habits, is favorable to the health and vigor of men and especially to the health and vigor of their intellect beyond any other conditions which can be offered them, that it not only gives pleasure for the time being but increases the subsequent capacity for happiness and the means of securing happiness.”iii

Olmsted warned that people deprived of time in nature due to busy lifestyles may develop emotional health problems such as melancholy or nervous conditions, foreseeing the perils of what we would now call ‘disconnection’ or nature deficit.

“The want of such occasional recreation where men and women are habitually pressed by their business or household cares often results in a class of disorders the characteristic quality of which is mental disability, sometimes taking the severe forms of softening of the brain, paralysis, palsey, monomania, or insanity, but more frequently of mental and nervous excitability, moroseness, melancholy, or irascibility, incapacitating the subject for the proper exercise of the intellectual and moral forces.”iv

Olmsted noted the habits of leaders and influential people who would take regular breaks in the outdoors such as parks, fields and mountainous areas, and claimed that they lived longer lives for doing so, an assertion supported by recent research on the effects of exposure to natural environments on health inequalities.v

“It is well established that where circumstances favor the use of such means of recreation as have been indicated, the reverse of this is true. For instance, it is a universal custom with the heads of the important departments of the British Government to spend a certain period of every year on their parks and shooting grounds, or in travelling among the Alps or other mountain regions. This custom is followed by the leading lawyers, bankers, merchants and the wealthy classes generally of the Empire […] there is a corresponding prolongation of vigor among the men of business of the largest and most trying responsibility in England, as compared with those of our own country, which physicians unite in asserting is due in a very essential part to the habitual cares, and for enjoying reinvigorating recreation.”vi

He believed that the beauty of nature affected the mind by reinvigorating the nervous system and noted that it can be difficult for many people to put into words the feeling they get when in nature, even when they are aware that it is having an impact. For Olmsted there is a connection between being impressed by your surroundings and the transfer of a positive message through the nervous system to the brain. A hundred years later the Kaplans postulated a similar notion within their Attention Restoration Theory describing the impact that nature has has on our mind and body by providing ‘soft fascination’, producing a calming and restorative effect.vii

“If we analyze the operation of scenes of beauty upon the mind, and consider the intimate relation of the mind upon the nervous system and the whole physical economy, the action and reaction which constantly occurs between bodily and mental conditions, the reinvigoration which results from such scenes is readily comprehended. Few persons can see such scenery as that of the Yosemite and not be impressed by it in some slight degree. All not alike, all not perhaps consciously, and amongst all who are consciously impressed by it, few can give the least expression to that of which they are conscious. But there can be no doubt that all have this susceptibility, though with some it is much more dull and confused shall with others.”viii

I’ve witnessed the same non-verbal reaction in people I work with outdoors when I ask what their experience of being in nature has been like. Commonly they smile, shrug, and then there is a silent pause where they reach for words but none come out. It is similar to the joyful expression a friend might have when they tell you that they have fallen in love. Near universally, people share that it feels liberating, freeing, less stifling, calming, supportive. When processed out in nature, emotions are allowed to surface, be addressed and then disperse, as if on a breeze. Whereas if they were in a room, clients have told me that they feel the emotions would have lingered and they’d have felt stagnant.

Many people experience time in nature as a form of mindfulness. Mindfulness is not new; such meditation has been practised for millennia. Olmsted too was a precursor to the modern Mindfulness movement; he claimed that constant attention and focus on future events, whether planning ahead, worrying about finances, or being concerned about influencing others caused mental fatigue, and he noted the power of nature to still the mind and to connect with the now, the present moment: “It is for itself and at the moment it is enjoyed. The attention is aroused and the mind occupied without purpose, without a continuation of the common process of relating the present action, thought or perception to some future end.”ix

Recent research using neuro-imaging to monitor the brain has found that walking in nature reduces ruminationx and increases meditative feelings.xi

Olmsted noted that natural scenery has the unique quality of simultaneously tranquilising and enlivening the mind,

“There is little else that has this quality so purely. There are few enjoyments with which regard for something outside and beyond the enjoyment of the moment can ordinarily be so little mixed. The pleasures of the table are irresistibly associated with the care of hunger and the repair of the bodily waste. In all social pleasures and all pleasures which are usually enjoyed in association with the social pleasure, the care for the opinion of others, or the good of others largely mingles. In the pleasures of literature, the laying up of ideas and self-improvement are purposes which cannot be kept out of view. This, however, is in very slight degree, if at all, the case with the enjoyment of the emotions caused by natural scenery. It therefore results that the enjoyment of scenery employs the mind without fatigue and yet exercises it, tranquilizes it and yet enlivens it [my italics]; and thus, through the influence of the mind over the body, gives the effect of refreshing rest and reinvigoration to the whole system.”xii

Olmsted wanted natural spaces to be available for everybody to enjoy, not just for the rich. He advocated access for the majority of society, including those to whom it would be of the greatest benefit, who tended to be excluded. He noted the controlling and patronising attitude of the governing classes toward the majority of the population. They believed that the lower classes lacked the capacity to appreciate nature as they had not developed the faculties to do so due to their constant involvement in physical labour. Instead, Olmsted argued, the governing classes promoted artificial pleasures such as amusement arcades, where the lower classes could consume monetised materialistic cultural artefacts. Indeed this still rings true today, as many of us are distracted away from the free natural world by expensive gadgets, flashing screens, insular headphones and the demands of social media. A phenomena well documented by Richard Louv in The Last Child in the Woods.xiii

Olmsted cautioned,

“It has always been the conviction of the governing classes of the Old World that it is necessary that the large mass of all human communities should spend their lives in almost constant labor and that the power of enjoying beauty either of nature or of art in any high degree, requires a cultivation of certain faculties, which is impossible to these humble toilers. Hence it is thought better, so far as the recreations of the masses of a nation receive attention from their rulers, to provide artificial pleasures for them, such as theatres, parades, and promenades where they will be amused by the equipages of the rich and the animation of crowds.”xiv

Many children I have worked with from inner city London have never had the opportunity to go to the woods, despite there being a surprising amount of woodland in the London area. When entering the woods for the first time they have asked with genuine concern, “are there bears in there?”. I have met children with no instinct for how to ‘play’ in natural settings. I once met a six year old girl who had been dressed by her mum for a day in the park in white leggings with diamanté trim. I helped her to climb a tree for the first time and she appeared to have no sense that such a thing could be climbed. When I asked her what she had been doing so far that holiday her answer was “watching TV”. Watching TV is all too often an all-day every day (in)activity for children in the holidays, particularly for those whose parents cannot afford to send their child to play schemes.xv

Olmsted reported in 1865 that women suffered from lack of access to recreation more than men, and those in agricultural work more so than women from professional classes. This speaks to the importance of the quality of experience within a natural setting. I have worked with members of communities with a recent history of working the land for subsistence that wish to distance themselves from nature as a means of having separation from a life associated with hardship, rather than associating nature with recreation.

In many ways, Olmsted was ahead of his time. On reading his report to his fellow commissioners in 1865 it was received with indifference and hostility and was quietly suppressed. However, despite being unappreciated at the time his efforts were not in vain. The US Library of Congress described Olmsted’s report as “one of the first systematic expositions in the history of the Western World of the importance of contact with wilderness for human well-being, the effect of beautiful scenery on human perception, and the moral responsibility of democratic governments to preserve regions of extraordinary natural beauty for the benefit of the whole people.”xvi

Olmsted extolled nature’s ability to promote emotional health and wellbeing, encouraged people to spend more recreational time outdoors and worked to ensure that areas of natural beauty were available for all to enjoy. And although his views on public access were not popular at the time, many years later people began to realise the legacy that Olmsted had bestowed through his work, in practice and philosophy.

i Olmsted, Frederick Law, Yosemite and the Maripose Grove: a Preliminary Report, 1865, http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/olmsted/report.html, accessed 23 August 2013

ii Gwang-Won Kim, MS et al, Functional Neuroanatomy Associated with Natural and Urban Scenic Views in the Human Brain: 3.0T Functional MR Imaging, Korean J Radiol 2010:11:507-513; Roe, J., Engaging the brain: The impact of natural versus urban scenes using novel EEG methods in an experimental setting, Vol, 1 2013, no.2, 93-104, http://www.m-hikari.com/es/es2013/es1-4-2013/roeES1-4-2013.pdf, accessed 5 March 2016

iii Olmsted, Frederick Law, Yosemite and the Maripose Grove: a Preliminary Report, 1865, http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/olmsted/report.html, accessed 23 August 2013

iv Ibid

v Mitchell and Popham, University of Glasgow and University of St Andrews, Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: an observational population study, Lancet 2008: 372: 1655-60

vi Olmsted, Frederick Law, Yosemite and the Maripose Grove: a Preliminary Report, 1865, http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/olmsted/report.html, accessed 23 August 2013

vii Kaplan and Kaplan (1989), The experience of nature: A psychological perspective, Cambridge University Press

viii Olmsted, Frederick Law, Yosemite and the Maripose Grove: a Preliminary Report, 1865, http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/olmsted/report.html, accessed 23 August 2013

ix Ibid

x Bratman et al, University of Stanford, Nature experience reduces rumination and subgenual prefrontal cortex activation, PNAS, July 2015, Vol 112, No.28, 8571

xi Aspinal, P. et al, School of Built Environment, Heriot-Watt University, The urban brain: analysing outdoor physical activity with mobile EEG, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 6 March 2013, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23467965, accessed 30 August 2013

xii Olmsted, Frederick Law, Yosemite and the Maripose Grove: a Preliminary Report, 1865, http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/olmsted/report.html, accessed 23 August 2013

xiii Richard Louv, The Last Child in the Woods, Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill, USA, 2010

xiv Olmsted, Frederick Law, Yosemite and the Maripose Grove: a Preliminary Report, 1865, http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/olmsted/report.html, accessed 23 August 2013

xv Beth Collier, Barriers to outdoor play and nature connection for inner city children, Institute for Outdoor Learning, Horizons magazine, No.63, 2013

xvi US Library of Congress, American Memory Project, The Evolution of the Conservation Movement, 1850 – 1920, http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/olmsted/, accessed 23 August 2013